Fully (Dis)connected

A decade sliding from online sickness to death

September 14th, 2025

Ten years ago this month I began to write Fully Connected, using the exponential spread of technology on our personal and working lives as the scaffolding for a wider argument about healthy connection and human networks in a social network age.

It was the year in which, prophetically, Sir Martin Rees, Lord Rees of Ludlow, wrote in a book called What To Think About Machines That Think that “There are chemical and metabolic limits to the size and processing power of organic “wet”) brains. Maybe we’re close to this limit already”.

Back then, in 2015, AI really was a far-off constellation, not the fully visible interstellar sci-fi reality it is today. Back then we were grappling with technology making us always-on : it was the year Facebook Messenger doubled its user base to 200 million; mobile-first apps started to really grow; and daily engagement with digital tools and technology meant not so much replacement by artificial intelligence but advancement in it: AI began, according to Google, to “open its eyes” that year.

Personally, in writing this book I began to really find and use my voice and opinion (at the tender age of fifty one). I highly recommend this particular high-wire act. Feel the Fear and do It Anyway: now there’s a good mantra, and that’s what I did.

Professionally, I began to outline to the business and policy community I had worked amongst for many years as an adviser, communications strategist and consultant that the social media revolution was in some ways not healthy and change was needed:

“Social Health - to maintain a balance of activity, mindset and connections, which can enhance well-being and productivity - can only operate in a culture that is receptive to forming new habits for new reasons. Being like the lightbulb which really wants to change”.

- Fully Connected: Surviving & Thriving in an Age of Overload

Politically, I called for The World Health Organisation to update its 1946 definition of health to include not just “social well-being” but “Social Health” and to signal that the politics of health had to factor in computer-dominated impacts on humans as much as the class effects of poverty on underlying health.

I argued that we need to widen our lens on society to how we live and work Now, not Then. Workathon’s World of Work and Workathon’s United State of Work project arose directly from Fully Connected and other books including The Nowhere Office) because how we live and work are literally, fully connected.

This is why I’m revising the book and updating it: The times have changed but the issues have not.

Illness as a Metaphor

I wrote Fully Connected after reflecting afresh on life and work during the years recovering from Pneumonia and Sepsis in which I neaerly died - contracted the year, as it happens, in which I first went on Facebook.

Illness, Susan Sontag wrote, is metaphor, and indeed it is. I wanted to illustrate the role in which illness plays in how we connect and disconnect: to show something through illness which we can learn from and relate to.

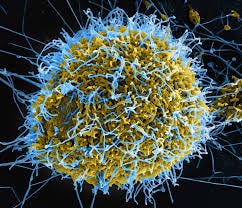

The Preface begins with my collapse on a beach in Aldeburgh, Suffolk, not knowing how ill I was. Chapter 1 “The Spreading Rate” begins with a story to illustrate how networks operate, how ‘fully connected’ we humans want to be and are whether we like it or not: the story of the spread of Ebola.

Well, that dates the book. Covid-19 was years away and by the time the book came out the least remarked aspect was the network science story of Louise Kamano bringing Ebola into Sierre Leone.

Sick Society

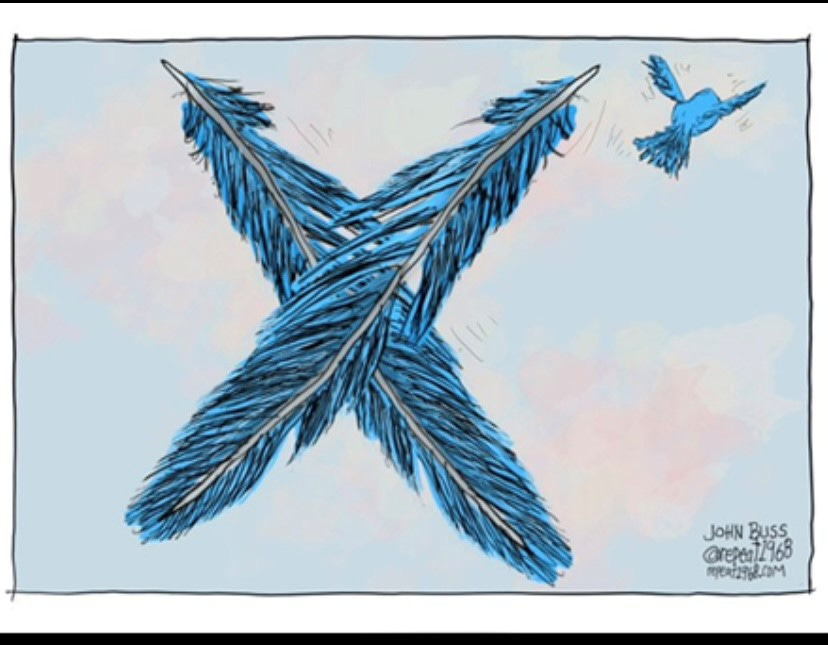

But ten years ago social media’s sickness was rising, and not really in full view: rather like, in fact, a pandemic before it gets into full swing. In 2015 live-tweeting X-Factor was a huge social phenomenon. It was seven years before Elon Musk took over and made a different X-factor: his 2022 takeover meant hate speech spiked by approx 50% on the platform.

Back in 2015 Germany signed deals with the major social media companies to withdraw hate speech in 24 hours. That seems quaint today. Less quaint and also in 2015 Facebook fundamentally changed its algorithm in a way which gave a greater platform (no pun intended) to the highest bidder for eyeballs.

The exponential rise of connection to social networks, the exponential rise in loneliness and mental ill health - all of these have happened in the last ten years since the world became more Fully Connected, not less.

The gunning down of Charlie Kirk this week has seen that fully connected societies turn into fully disconnected ones when they can use social media to spread the virus of hate on all sides.

There isn’t enough time now to mourn a senseless, wrong death before recrimination, blame, and the risk of retribution rushes in. Certainly hate speech seems to have cost free speech its life in America - and life itself on campuses from Columbia to Utah.

Time is of the Essence

Something else is being killed. Our ability to reflect and to pause and to make sense. Time rushing by isn’t new: This summer I reflected on one of my favourite writers and the quote I actually open Fully Connected with:

“I am OK but have too much to do - crazy things I said I’d do long ago seem to be crowding around….I can’t get at those long calm necessary periods of time”

- Iris Murdoch

We must re calibrate not only connection but speed and think on what it means to be human - and humane. This is the advantage of the “wet brain” of Sir Martin Rees’ essay: A pulsing, living, feeling organism.

One more thing happened ten years ago which may have been a harbinger: A connection between the rise in aggression online in games and offline was cited by the American Psychological Association.

We can preserve this commitment to the connection to living as humans and not game show characters who kill with words and guns: can’t we? We must hope so.

Let me know what you think, won’t you.

Julia